Can you teach me about Pol Pot?

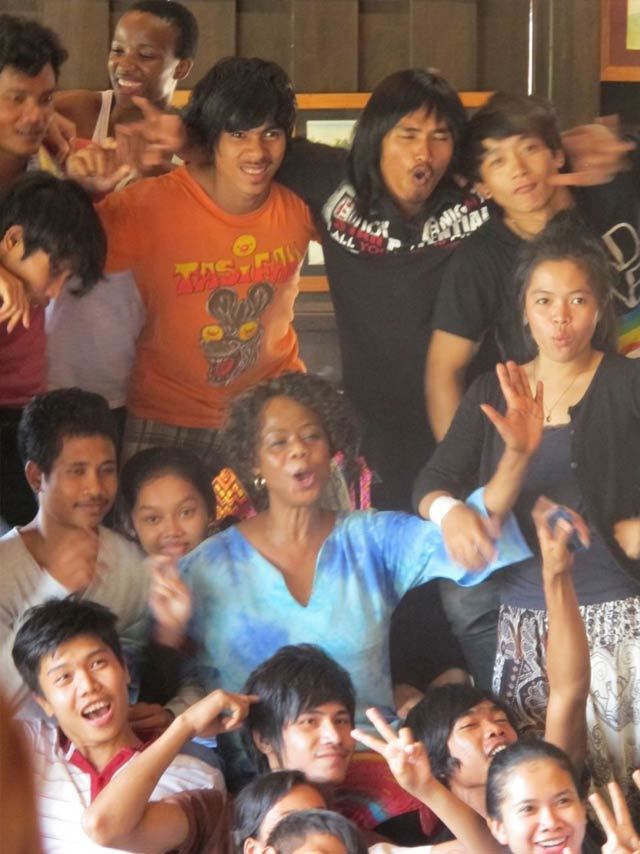

Jackie, Nick, and I have just returned from Battambang, Cambodia, where we were invited by an extraordinary collective of artists, themselves former child war orphans, who take care of at-risk kids between the ages of 6 and 23. The village of artists is called Phare Ponleu Selpak (The Brightness of Arts). It is a place of hope. The students we worked with are part of the Phare Ponleu Selpak and have been professionally trained as circus performers.

These children are storytellers; their language is circus. To work with them, we invited Andrew Buckland, Thembi Mtshali-Jones, and Sibu Gcilitshana from the Truth in Translation cast to join us. We were there to teach them acting and to create a story about their recent perceived and imagined history. We were invited because we had experienced such a journey personally and felt we could help these young performers probe into places where, at the moment they are hesitant to go and where their teachers, quite reasonably, might be hesitant to take them.

So all of us were searching for a theme, a question that had to be asked to create this production.

When we started our workshop a young boy asked, “Could you please teach me about Pol Pot?” I think he knew about Pol Pot. Why would he ask this question of a foreigner? Is it because he feels like the story of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge should be clearer in his mind? Is it because of what he’s heard, what he’s pieced together from his elders’ whispers and off-hand references that never made any real sense (eat your rice…we died for that rice)? Is it because these kids feel a kind of shame that he doesn’t understand? Or is it that Pol Pot just wouldn’t make sense to a kid?

Is it, possibly, he feels that there is something out there that has to be forgiven? Or is it perhaps because Pol Pot was Khmer, just like him?

These kids are amazing performers. They have pride and power in their bodies and their athleticism. They will be listened to by world audiences who also have come through history of violent conflict. We ask ourselves, “Can they begin to deal with an horrific past that is not their first hand experience and yet…is absolutely theirs?” Yes, they talk about it openly in buzzwords, but only in that innocent politically correct kind of way that makes its way into textbooks and seems to be expected. Or, do they read it on the faces of tourists like ourselves who are looking for answers, or, for better or for worse…looking for a play?

Probably all of the above. But what interested us most was how they read it in the eyes and the sighs and the avoidance of real engagement they receive from their elders.

We start with warm ups. But almost within hours they allow us, even encourage us, to take them to a place where they will have to meet these imagined memories. Some are shy. Some are brazen. All are totally in the moment. At night, when we recap the day’s experiences, we ask ourselves, “Do we have a right to do this? Shouldn’t these kids be allowed to move on without opening wounds that are not really theirs?”

Days pass. These kids are amazing. Brave and joyful and fantastically talented. We have tentatively decided to call our production “Landmines”. As real things, they are all over the place. People still get blown up with regularity. The thought occurred to me watching their work—these magnificent bodies could create one hell of a great “explosion” on stage. The metaphor was good, the structure promising: the simple story of the next generation having to unearth the horrors of the past like some infantry soldier asked to dig up land mines with zero experience. Is it wrong of us to come in and hand our inexperienced troops a spade and say, “Start digging!”? What if they hit an historical or emotional landmine that blows off one of their emotional body parts?

But then we come back to the question that brought us here: “What if they don’t dig? What if those land mines stay buried?” Then every one walks on egg shells for the next 50 years until we forget that they are even there…. and some madman or arms dealer with an agenda decides to remind them of what was done to them sometime way back then. BOOM!

As the Global Arts Corps, we create our plays to disturb denial. We make them to create mirrors for audiences, for one culture rising out of violence to share their need for healing…or their fear of it. We create them so victims and perpetrators alike can share their fear of dropping their masks, and perhaps even explore why they can’t give up the idea of vengeance and revenge.

But are these kids in denial? How could they be? They weren’t even there when “IT” happened.

…but what if they don’t dig? In the production we are creating in Belfast, we were told that no one wants to dig into the past now that they have ratified a peace accord. So why, since the peace accord was signed, are there 38 new sixteen-meter walls with barbed wire barriers to separate themselves from each other? In Kosovo, where we are creating another production, they go back four hundred years to find their entitlement to kill.

“Tell me about Pol Pot.” How did he get the way he got?

Are they asking, “Could we become the way he became?”

We talk about forgiveness, but should we not be talking about shame—how shame leads to denial and about how denial becomes an addiction? Denial helps to develop sanitized versions of history that insist that we are neither victim nor perpetrator. Denial helps us forget. Denial creates a mask that is almost impossible to take off.

As actors we are asked to drop our masks every day. As we rehearse, we find ourselves reconciling many truths because we have to adjust our masks for the sake of finding a joke or a dramatic moment. We also create new risks as we do it. We look at each other differently, even if we still disagree across cultural and religious divides. This is the professional actor’s craft—it’s what we do every day on stage.

Do we have a right to do it in real life, with other people’s histories?

If someone ever asked forgiveness for their past, would these kids know how to give it? These are questions that we wrestled with over the week, circling the various truths, the various possibilities. This is just the beginning of our process here in Cambodia; there is a long journey in front of us still. Whatever the answers are, they will come from these brave circus performers. And we will be listening.

– Michael Lessac